About the author:

Hari Seshasayee, Global Fellow, The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; Trade Advisor to the Colombian Government

The argument that “you are either with us, or against us” has been repeated throughout history. It is found in religious texts like the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and the New Testament; in literary works like George Orwell’s Pacifism and the War and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22; by numerous leaders and politicians, from Vladimir Lenin and Benito Mussolini to George W. Bush; and even in film franchises like Beauty and the Beast, Star Wars and X-Men.

Yet, as imperious as it may seem, this argument is often a false dichotomy – one that artificially limits the options available to just two sides, when there could be more options. This certainly seems to be the view of India’s Foreign Minister Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar regarding the ongoing war in Ukraine. At a recent conference in Europe, he asserted, “just because I don’t agree with you, doesn’t mean I’m sitting on the fence; I’m sitting on my ground…Europe has to grow up out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems, but the world’s problems are not Europe’s problems.”

Some have perceived India’s position as one of neutrality, particularly because New Delhi has not condemned Russia. Neutrality during moral crises often has a negative connotation. Dante Alighieri condemns neutral angels and humans to the “entrance-hall” of Hell; Martin Luther King Jr. echoed this sentiment while opining about the Vietnam War, “that the hottest places in hell are reserved for those who in a period of moral crisis maintain their neutrality,” and even Archbishop Desmond Tutu opined that in the case of Apartheid South Africa, “if you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

This partially explains the level of censure that India has faced for its present stance on the war in Ukraine. Not only did many in the West rebuke India; one high-level United States official even warned that India would have to face certain “consequences” if it continued doing business with Russia despite US sanctions. Others have questioned why India has not condemned flagrant violations within a country’s sovereign borders, given its own experience with territorial disputes and wars.

Still, it may be worth remembering that positions of morality – specifically one with international actors – evolve over time. In the case of Ukraine today, the rhetoric of countries today is far more critical towards Russia than when the war initially began. India’s position too, could gradually evolve over time. However, India is not alone: a sizeable portion of the world is reluctant to take a firm stance against Russia, and tellingly, as many as 35 countries abstained in a UN vote on March 2, 2022, to condemn Russia for attacking Ukraine.

New Delhi’s Positions on Russia and the Far-Reaching Impacts of the War

Russia did, in fact, invade Ukraine in an act of unprovoked aggression. Such violence against sovereign states should not be acceptable in a post-colonial world.

So, why then has India not been swift in condemning Russia?

Perhaps the best way to approach this answer is to look at it through the lens of time:

1. The past: India has enjoyed a close, strategic partnership with Russia and the erstwhile Soviet Union. The Soviet Union supported India during some wars and armed conflicts, particularly by providing India with MiG fighter-aircrafts during the Sino-Indian War of 1962. At the same time, the U.S. often sided with Pakistan. India also received significant support on the nuclear front in the 1980s to construct “two 1,000-MW light-water reactors and provide enriched uranium fuel for the reactors’ entire operational life,” in addition to leasing a nuclear-powered submarine. Consequently, the Soviet Union became one of independent India’s most important allies, and its successor, Russia, transitioned into a similar role.

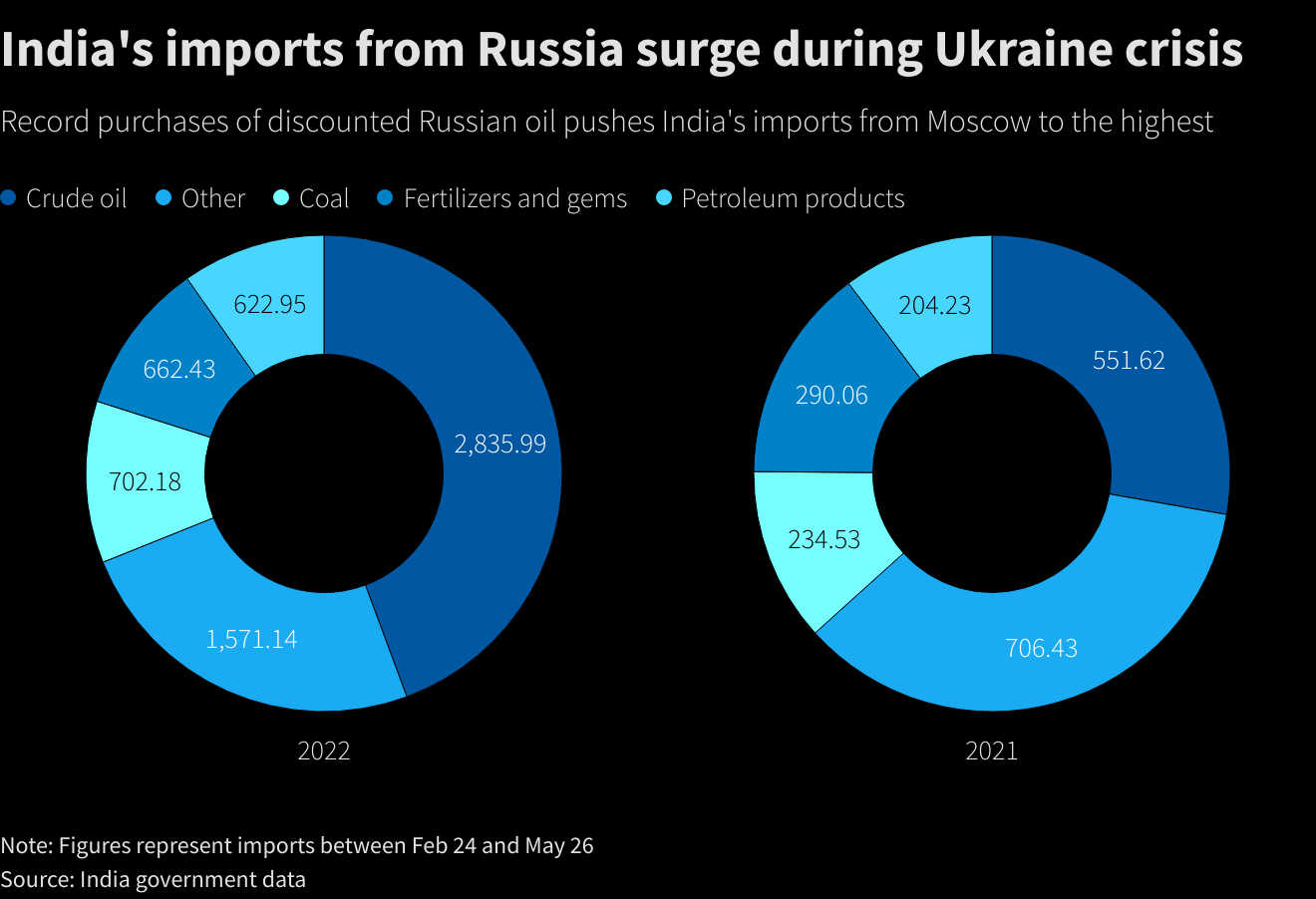

2. The present: Whether or not policymakers in India and abroad like it, India’s dependence on Russian arms today is indubitable. About 62% of India’s arms imports since 2010 come from Russia. More importantly, the vast majority of the current inventory of military hardware, aircrafts, ships, tanks and weapons systems used by India’s army, navy and air force are of Russian origin, and depend on Russia for spare parts and servicing. Additionally, India relies on Russian support to run some nuclear energy plants, and imports a reasonable amount of fossil fuels, specifically oil and coal.

3. The future: This specific element has been absent in most analyses of India’s position on the war in Ukraine: how does India view its relationship with Russia in the future, and more importantly, a more distant, post-Putin future? The answer lies partially in being able to depend on Russia as a source of affordable arms and energy supply, but more importantly, New Delhi does not want to risk alienating Russia due to its close ties to China. Surely, India does not want an antagonistic relationship with both China and Russia in the future. Western sanctions on Russia have illustrated the vulnerability of “the Rest” in a US dollar-dominated world, and the possibility of a RIC (Russia, India, China) grouping to limit such exposure is not to be dismissed.

(Source: www.reuters.com)

Although New Delhi has not condemned Russia, it has not ignored the conflict altogether. The official statements by India’s Foreign Minister and Prime Minister have both emphasized an “immediate cessation of violence and end to all hostilities,” adding that “India has always stood for peaceful resolution of issues and direct dialogue between the two parties.” India’s Prime Minister also called both Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Russian President Vladimir Putin, twice (in February and March) in a failed attempt to promote dialogue between the two countries.

More recently, however, the language being used by New Delhi has changed, from one of peace and cessation of violence to increasing concern about the global impact of the war on rising food and energy prices, on global value chains as a result of sanctions on Russia, and the disruptions in wheat, vegetable oil and energy markets. In his recent visit to Denmark, India’s Prime Minister emphasized the “destabilizing effect of the conflict in Ukraine and its broader regional and global implications.”

India continues to engage with Russia and imports modest yet noticeable quantities of oil and coal from Russia. Although this oil is bought at heavy discounts of up to $40 below Brent prices, India’s foreign ministry insists that “energy purchases from Russia remain minuscule in comparison to India's total consumption.” India also points to a more urgent reason for continued energy imports from Russia: to reduce the burden on its own people, who are now paying far more at petrol pumps and for staple food like wheat, vegetable oils and cereals.

(Source: www.ndtv.com)

Active Non-Alignment vs Strategic Autonomy

The collateral, global impact of the war in Ukraine is palpable in India: petrol prices have reached record highs, and government controls on petroleum prices have resulted in deep losses for publicly owned oil companies. Thus, it is useful to contextualize India’s positions through the lens of the concept of Active Non-Alignment (ANA) put forth by Jorge Heine, Carlos Fortín and Carlos Ominami.

Although ANA was initially envisioned for Latin America, it is relevant for understanding India’s foreign policy calculations. New Delhi no longer views geopolitics as unipolar; it views the world as multi-polar, and more importantly, believes in “multi-alignment” and “strategic autonomy,” an evolution from its historical position as one of the leaders of the non-alignment movement. The approaches outlined by Heine et al. in their initial definitions of ANA could also be applied to India: “strengthening regionalism” in South Asia is amongst New Delhi’s highest priorities; “reorienting foreign policies” to adapt to a constantly changing, multi-polar world is a constant challenge and objective for India; “new international financial institutions” remain an important pillar of India’s geoeconomic policy, illustrated by India’s role as a founding member of the New Development Bank; however, India veers away in the last approach to ANA, to keep “an equal distance from both superpowers” (i.e. the U.S. and China), given its participation in the Quad grouping and its increasingly close relationship with Washington.

This also helps explain New Delhi’s probable, future positions on the war. For one, New Delhi is highly unlikely to join any war effort, whether in condemnation, with material aid or military supplies: its priority is to safeguard its people from the economic impacts of a protracted war. Unfortunately, despite its sheer size and its great-power aspirations, India has little influence or control in determining the course of this war. Siding squarely with Ukraine and the West will sideline India’s most important defense partner, Russia; and overt silence on Russian aggression will disgruntle the West, and particularly India’s partners in the Quad. India has little choice but to continue walking this tightrope.

The Endgame on Sanctions and India’s Future Positions in a Multi-Polar World

Looking beyond India’s positions on the war, we are left with some important questions regarding its global impacts: How much more will the war, as well as the sanctions on Russia, destabilize global markets? And in the long run, how does one separate the opprobrium against Putin the leader, from Russia the sovereign nation?

Esfandyar Batmanghelidj and Francisco Rodríguez offer some pragmatic explanations on sanctions, noting that they cause “severe dysfunction by creating acute supply-side disruptions within free markets.” More importantly, Batmanghelidj and Rodríguez suggest four steps that could diminish the impact of sanctions on the global economy: first, sanctions should be targeted at a small set of political elite, not the common people; second, sanctions must shield vulnerable populations, including migrants in Russia, from the fluctuations in foreign currency markets that hamper their saving and spending capacity; third, encourage alternative suppliers to increase exports, while protecting the flow of vital food commodities from Ukraine and Russia to the world; finally, they suggest that “restrictions on international payments systems should be reassessed and circumscribed as much as possible, given the potential knock-on consequences for global economic stability.”

The question of a post-Putin Russia is harder to answer. After all, the world will – at some point in the future – see a post-Putin Russia, and it would be unlikely that Russia remains a pariah even then. Unfortunately, one of the gaping failures of the current world order is that common citizens of Cuba, Iran and North Korea, and now Russia, bear the brunt of international sanctions, even while their regimes continue to remain firmly in power. If sanctions fail to remove the regimes they target, what exactly do they achieve?

Perhaps one final thesis is worth examining at this juncture: What is India’s position in the future of this multi-polar world, specifically one that is led by the U.S. as well as China? We need to look no further than Minister Jaishankar’s remarks at the same European conference: he remarked that India is “a democracy, a market economy, a pluralistic society,” and also a member of the Quad; that should certainly tell us something about the road India is taking.

(Views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Colombian government.)

Please note: The above contents only represent the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views or positions of Taihe Institute.

This article is from the June issue of TI Observer (TIO), which is a monthly publication devoted to bringing China and the rest of the world closer together by facilitating mutual understanding and promoting exchanges of views. If you are interested in knowing more about the June issue, please click here:

http://www.taiheinstitute.org/Content/2022/06-30/1115477342.html

——————————————

ON TIMES WE FOCUS.

Should you have any questions, please contact us at public@taiheglobal.org