U.S.-China Relations: Tracing Systemic Differences

September 03, 2021

About the author:

Thorsten Jelinek, Senior Fellow and Europe Director, Taihe Institute

Amid the intensification of Sino-U.S. antagonism in recent years, a fundamental difference in approach to the ideological pillars of democracy and capitalism has emerged between China and the U.S. While the latter understands these as “ends” that, in the words of Francis Fukuyama, should become “global norms” at the end of the Cold War because of its perceived superiority, the former interprets these concepts differently, arguing that American democracy is not appropriate for China’s own national situation; it does not operate according to American. standards and therefore should not be assessed based on this system.

1. Based on your knowledge about China, what do you think “democracy” means in the Chinese context? What is the role of “democracy” in Chinese political culture?

The extent to which China is or should become a democracy has been long debated in China itself. Liberalism, which still dominates but is increasingly cast into doubt within Western democracies themselves, has also been instrumental in China’s own modernization and reform. Yet, China has never taken liberalism and democracy as an end for itself or as the “end of history,” but rather as a pragmatic tool to bring wealth to its people and transform the economy, while “escaping shock therapy.” Performance and results, and not procedures, are rather seen as a democratic value.

In China, democracy means that the government does not act in its own self-interest, but in the interest of the Chinese people, which primarily means cushioning the disruptive impacts of global capitalism and the country’s own rapid transformation. Over the past four decades, China has successfully balanced the “hedgehog” of market dynamisms with the “snake” of social cohesion. However, the country’s development success is not simply due to the import of Western liberalism and being a late-emerging economy, but also because of the continuation of a strong state, the Communist Party’s egalitarian and collectivist ethics, and a culture that reflects the old “Guanzi symbiosis” between the state and the economy that had already guaranteed ancient China long periods of stability and prosperity. Guanzi is the name of a series of texts that were compiled by the scholar Liu Xiang to address the need to calibrate state–market relations during the Warring States era. The government’s demonstration of such collective responsibility and balancing of interests can be summarized with China’s old concept of benevolence, which is equivalent to a modern democratic value. The most recent policy shift from “get rich first” to a focus on “common prosperity for all” signals the Chinese Communist Party’s attempt to balance between market dynamism and social cohesion, the latter of which they are focusing now.

Source: https://unsplash.com

However, the party-state does not rely on ancient virtues to govern 1.4 billion people. It has institutionalized mechanisms and processes that help identify the demands and needs of the Chinese people and respond to a rapidly changing and uncertain environment. The Communist Party has 95 million members, which represent roughly 6.8% of China’s population. In comparison, 0.5% of Germany’s population are members of one of Germany’s parties, from which future politicians emerge. The Party’s Central Committee, which carries out the decisions of the National Party Congress and from which the highest-ranking party members are selected, has a 62% turnover rate every five years to ensure fresh representations and ideas. Unlike in the past, many Central Committee members have a technical or engineering background to reflect the skills needed to understand and effectively address current development challenges. The state also has mechanisms to directly interact with the various stakeholder groups and regions without which it would be impossible to govern such a large country.

2. What are the key differences between the American-style democracy and the Chinese-style democracy?

There are fundamental differences between China’s socialist democracy and how the West and the U.S. practice liberal democracy. The dominant Western conviction is that China has no democracy at all. Some depict China as a Marxist-Leninist one-party system, whose ancient history and culture of dynastic changes is often neglected. Others conveniently reduce China as an authoritarian capitalist country, which fails to explain the social and political control the government exerts over market mechanisms and “big capital.” The state does not simply “conspire” with capitalism, but clearly intervenes when markets crumble or fail and when pollution and inequality reach unsustainable levels. This explains the recent shift to a focus on “common prosperity for all.”

Political economist Francis Fukuyama uses three dimensions to summarize the pillars of the modern Western government, which help to discern the differences between the West and China: rule of law, legitimacy, and bureaucracy. First, China practices an “enlightened legal system,” but not universal law. There is no division and full institutionalization of power, and the Communist Party remains the primary source of power. The application of Chinese law is rather procedural than universal. China’s legal practices can be described as “rule by law” or “rule-based decision-making.” Second, the Party and the government are not legitimized through general elections, but by Communist revolution, economic development, government performance, and the country’s long history of centralism and unity. As the Chinese government takes a longer-term view than governments in the West, some argue that the Chinese system intrinsically demonstrates greater accountability. Over 90% of China’s population are optimistic or positive about China and the central government’s performance, whereas approval ratings of Western governments are usually between 20 and 45%. Lastly, China operates and rules through a strong and complex bureaucracy that has developed over centuries. Fukuyama even argues that China was the first civilization that developed a modern state, which was hierarchical, uniform, and impersonal, around 221 BC. Although constantly changing and adapting to new conditions, China’s party-state bureaucracy is advanced and effective compared to those of other late-emerging economies. However, from a Western and Weberian perspective, the Chinese state bureaucracy is not fully rationalized and tends to sustain irrational types of domination.

Source: Image by fotogestoeber/Getty Images

China has decided for itself that a democracy based on freedom of expression and association, democratic control through elections and a multiparty system, and the separation of powers to sustain an independent judiciary, is not suitable for China’s history, culture, and current condition. Given the West’s myriad challenges, including its prolonged legitimacy and trust crisis, increasing populism and nationalism, fragmentation of social cohesion, and inability to respond more effectively to shocks and crises, it is rather questionable whether Western democracy is more suitable for China. Despite China’s economic and technological might, its per capita income will still only be 50% of the U.S. by 2049. For China, to rely on a procedural government system based on which Western democracy is grounded could rather endanger China’s long-term development.

3. What creates such differences? In other words, why might the American-style democracy function in one society but not the others?

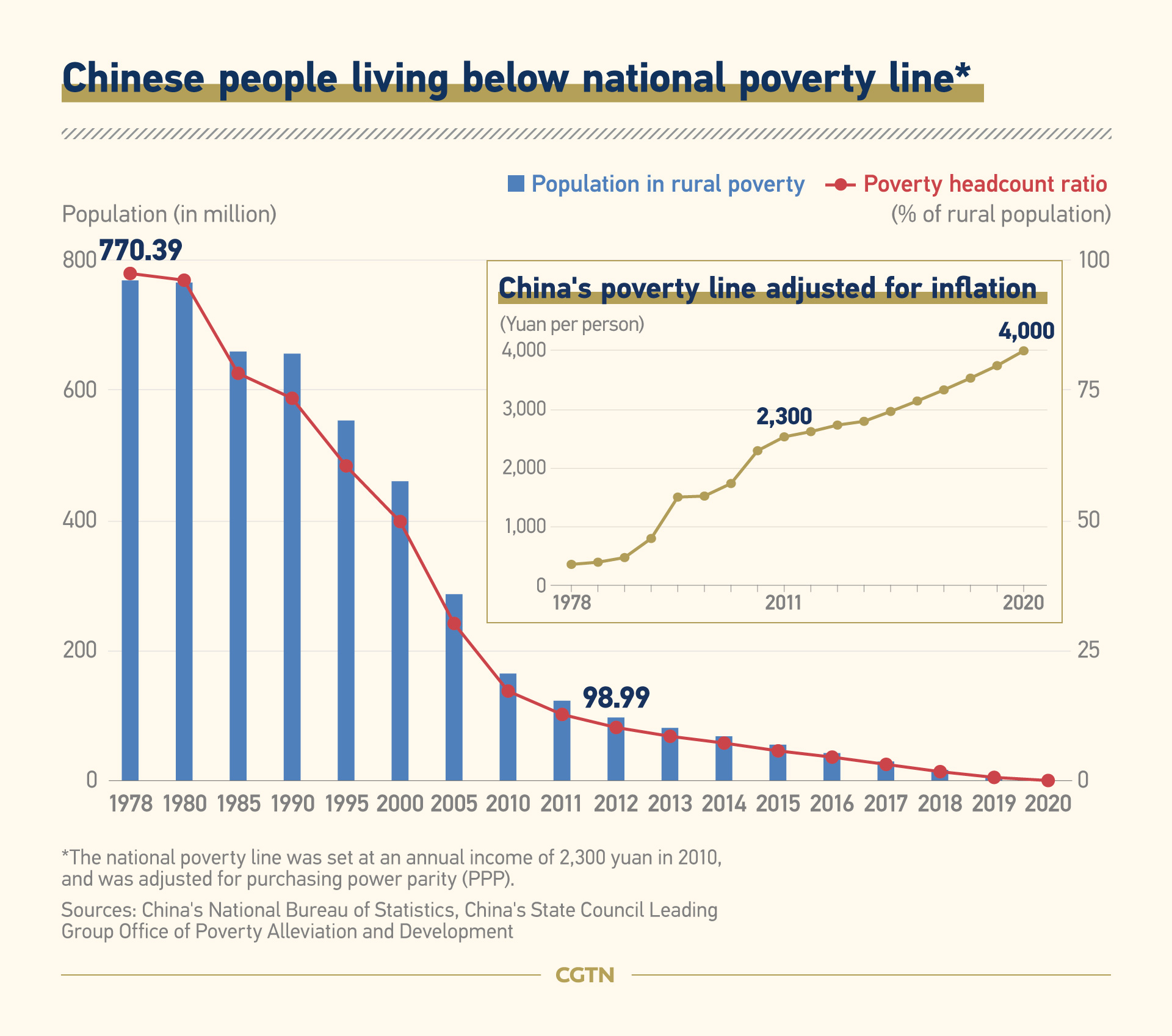

While the ideals of Western democracy and human rights can be deemed universal, the path toward reaching those ideals is not universal but depends on specific historical, cultural, and actual conditions. China has lifted millions of people out of poverty —a fundamental human right — and has achieved such poverty alleviation without becoming a liberal democracy.

While the world copes with global capitalism, ubiquitous digitalization, climate change, and the pandemic, each region responds to those trends and threats in its own idiosyncratic way. The U.S. approaches the challenges from an individualistic perspective, China from a collectivist one. The challenges are the same, but the approaches are diametrically opposed and are causing systemic tension.

Besides, we cannot be sure that any governance system is best equipped to deal with future challenges. With or without “shock therapy,” China has reached a level of inequality that is symptomatic for capitalist transformation, one that is also experienced in Russia. China has decided and has the legitimacy to exert more state control over the market and society to address the challenges of its aging population, severe inequality, and climate change. And the West is experiencing a “renaissance of state intervention” to respond and deal with global challenges, which clearly suggests that the liberal capitalist order has reached its limit and is unsustainable in its current form. There is a clear reversal of Ronald Reagan’s famous dictum that “government is not the solution to the problem; government is the problem.” Obviously, now government must become a solution to the problem.

Source: https://news.cgtn. com

4. How would you approach Francis Fukuyama’s argument that democracy is the best form of governance and would become the global norm at the end of the Cold War? Do you think democratic capitalism has a direct effect on development and growth? What is the causality between economic development and democracy as a political institution?

Fukuyama’s “end of history” meant that liberal democratic capitalism was there to stay after the Fall of the Berlin Wall. The goal was to repair and optimize itself, and eventually assimilate other non-democratic, authoritarian countries. His idea also meant that the West was able to predict or determine history, and that there was nothing external that could have influenced the cause of history. Obviously, Fukuyama’s “end of history” was short-lived. Neither the welfare state of the 1990s nor the push towards post-Keynesian policies in the early 21st century helped to avoid the steady rise of income and wealth inequality in the West and at the global level. Climate action was not yet part of that history or the mainstream political agenda. Yet, capitalism turned into hyper-globalization, causing a series of shocks and started eroding all the cornerstones of Bretton Woods. Today, Western democracies are under threat, nationalism is on the rise, and global supply chains risk decoupling. While identity politics have become an essential part of liberal democracy, it has also undermined governance efficiency and the formation of political majorities that could carry out necessary reforms in the West. According to Dani Rodrik’s “inescapable trilemma of the world economy,” the local democratic process was trapped by the “golden straitjacket” of hyper-globalization anyway.

Today, and certainly because of the pandemic, the more visible and destructive impact of climate change, and social unrest, many young Americans express their dissatisfaction with neoliberalism and even demand more of “socialism” that strives to achieve a balance between individual rights and individual responsibilities. However, during the 30-year anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall, in 2019, and still prior to the global pandemic, Fukuyama said that Western liberal democracy is still the only viable political system in the world. Neither the Arab world, Islam, the African continent, nor Russia offers a viable alternative that will ensure prosperity, dignity, and public participation in the political process. The only possible alternative, according to Fukuyama, is China. But he was skeptical about China’s long-term ability to develop as the country experienced its first economic crisis and recession that could fundamentally undermine the legitimacy of China’s party-state apparatus. To Fukuyama, the rule of law and abstract state institutions as well as elections are the procedural means in the West to regain public and popular legitimacy. Yet, he underestimated that President Biden would continue President Trump’s neopopulist politics.

Berlin celebrates the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Wall

Source: https://about.visitberlin.de

In 2020, Fukuyama proposed another way to compare the performance of governments in addressing the global pandemic and other potential future shocks. He did not question Western democratic institutions and processes, but looked at the level of state capacity, social trust, and leadership performance to explain the effectiveness of prevention and recovery measures to make sense of China’s relative success. “Countries with dysfunctional states, polarized societies, or poor leadership have done badly, leaving their citizens and economies exposed and vulnerable.” This helps to explain why the Trump administration failed miserably in fighting the pandemic regardless of China’s initial delays and lack of transparency, and why China performed exceptionally well. Not knowing whether President Biden would be elected, Fukuyama further concluded that countries “doing well on all three sides will come through the crisis relatively well, implement reforms that make them stronger and more resilient.” In this way and at least in relative terms, China can be confident in its governance approach and the strong solidarity from the Chinese people. Based on Fukuyama’s categories, it’s rather questionable whether President Biden can resolve the damage done by the previous Trump administration. The problems are much more about the structure rather than the individuals. With many unassigned senior government positions, Biden’s administration severely lacks government readiness, which rather impedes progress on important issues. At this stage, US democracy cannot provide much certainty about how the country fares in the post-Biden era.

Source: https://www.pexels.com

5. From the perspective of third-party countries, do you see Sino-U.S. ideological and structural differences as irreconcilable?

As economist Nouriel Roubini observed, the neoliberal agenda of previous US presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama supported the emergence of an oligopolistic economy in the U.S. that exacerbated inequality. This both bred and was interrupted by Trump’s neopopulism, which has become pronounced under Biden’s Presidency. Unlike many democrats’ initial belief that President Biden would somehow return to the neoliberal politics of the Obama administration, the Biden administration seems to have adopted Trump’s nationalist and protectionist trade policies. Trump’s unilateral trade war against China has turned into a “whole-of-government” containment approach against China. While the relationship between the United States and China unfolded as a regression from presumptuous optimism and rapprochement over skepticism to attempted containment, the diplomatic relationship between the U.S. and China has already reached a low point under President Obama, who sought to contain China by rebalancing military forces and excluding China from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The Biden administration now seeks to complete Obama’s “pivot to Asia” and it appears like they can achieve this by relying on bipartisan and public support. Though liberal capitalism has come under attack within in the U.S. and Europe, when it comes to dealing with China, those values continue to remain protected even by the political Left. In other words, while the Left demands more state intervention to address income inequality, it sees the Communist Party’s recent shift toward “common prosperity” is as the Party’s attempt to strengthen its legitimacy or an arbitrary act of state interference.

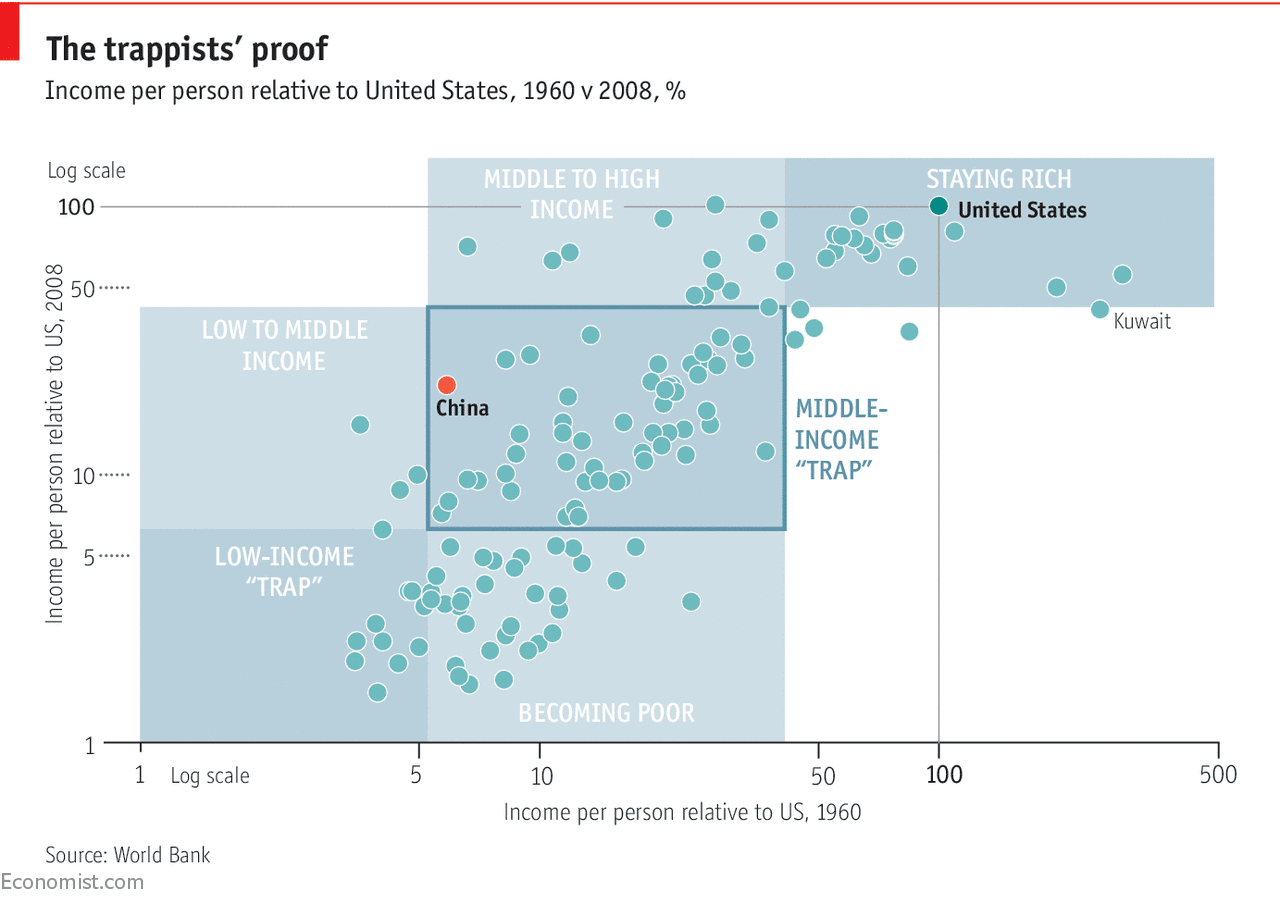

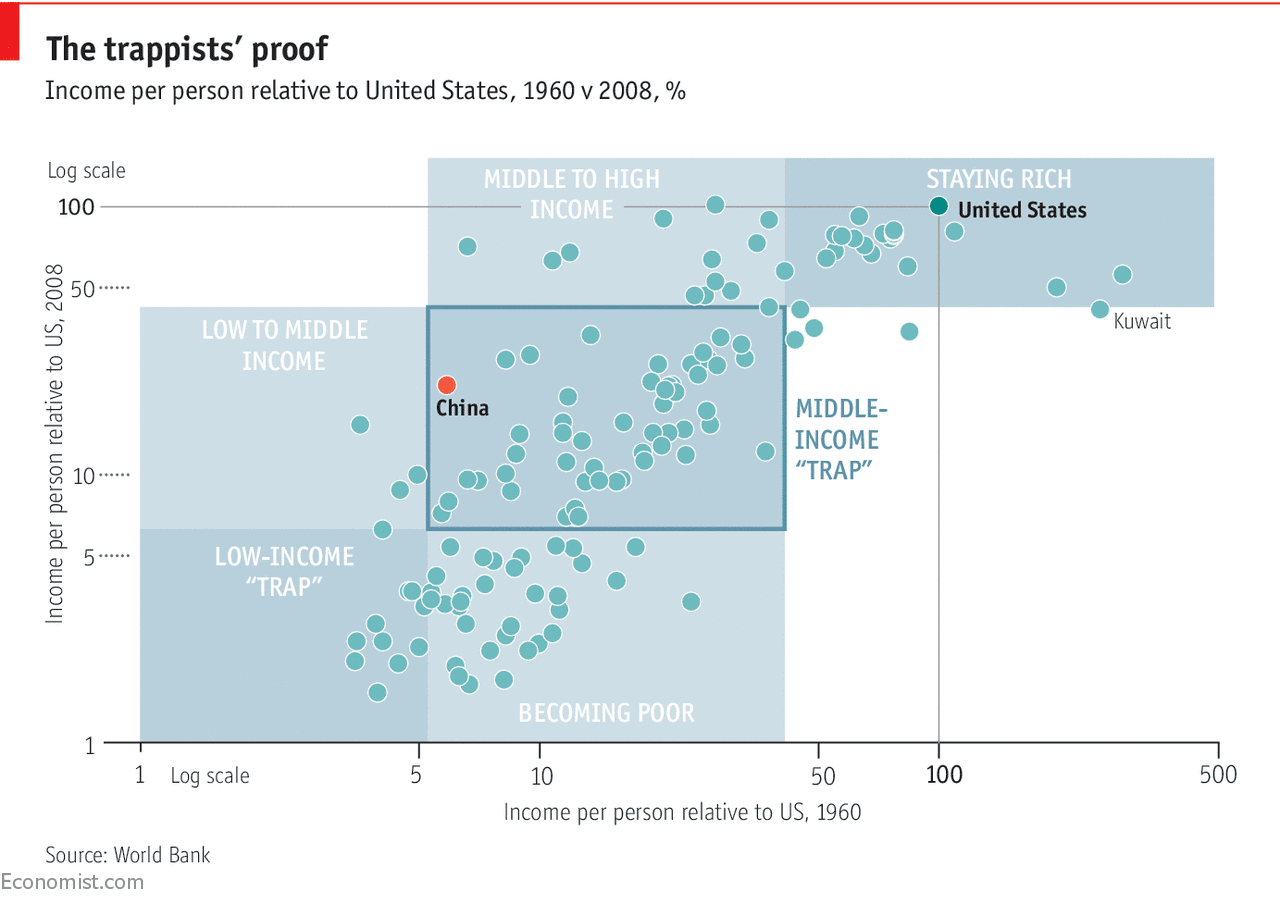

Source: https://www.economist.com

The debt-trap based economic model of the U.S., which has become more unsustainable under the Biden administration, makes the country more vulnerable to external shocks while a myriad of other domestic issues has left little space for a change in Washington’s foreign policy behavior. American global interventionism will remain justified based on protecting human rights, the rule of law, and fair economic competition. The U.S. established the current order and does not have much choice but to protect it to sustain its economy. China itself faces many domestic challenges, but for the West, China serves, again, as a justification to recover Western liberal values globally.

6. In what ways does the recent deterioration of Sino-U.S. relations affect world politics and other countries? How important is it for the two to transcend their ideological/structural differences?

The deterioration of Sino-U.S. relations has further divided and fragmented global politics and relations, but without global collaboration, humanity won’t effectively address existing global challenges. The fragmentation can be seen in areas including economy, security, technology, and ideology. Such fragmentation risks undermining the much-needed post-pandemic recovery.

More fundamentally, 30 years of globalization and hyper-globalization have compromised national sovereignty and democratic politics. Thus, regaining national or regional sovereignty has become the default response and industrial political agenda. The demand for sovereignty clearly risks turning into protectionism. Economic pressure and national security concerns make it less likely that the U.S. or China will transcend their differences. In addition, while the United States sticks to its exceptionalism, China continues to emphasize its unique characteristics.

7. What do you think are some of the key factors that obstruct mutual understanding?

Deep-seated interests, mutual fear, and Western arrogance are among the key factors that have obstructed mutual understanding and further deteriorated Sino-U.S. and Sino-Europe relations. Since the formation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, its sovereignty and national borders have been contested by the United States. As China is on the way to become the largest economy by 2030 and trying to avoid the “middle-income trap,” it has no choice but to protect its interests domestically and internationally while the West seeks to revamp the liberal order by excluding China. China’s current strategy is perceived as protectionist and assertive, breaking with the previous strategy of “hiding her strength” and “biding her time.” In addition to such mutual fear, fierce competition and competitiveness do not offer much space for collaboration, especially since China is increasingly becoming an innovation-driven economy, which used to be the prerogative and sole achievement of the West. Against this backdrop, there is no reconciliation in sight as of right now. Quite the opposite, the United States actively pushes four differences while seeking to rebuild its alliances against China: building (1) a democratic alliance to prevent China from changing the global order; (2) a geostrategic alliance to contain China’s geopolitical rise; (3) a global economic alliance to curtail China’s economic and trade influence, and (4) technology and standards alliance to prevent China from determining the technological heights of this century. While non-Western countries and especially China’s neighbors do not want to take sides, the relationship between Europe and China has come to a hold. This is mainly the result of US foreign politics since the Obama administration.

Source: https://www.japantimes.co.jp

8. In light of the current state of Sino-U.S. relations, how should the countries approach the ideological and structural differences, respectively? What can or should be done to preserve the resilience of Sino-U.S. relations?

Our future depends on, as historian Yuval Harari pointed out, the choice between “nationalist isolation” and “global solidarity.” The former will prolong our current crisis, lead to new crises, and further erode trade, foreign, and people-to-people relations. It will increase the risk of asymmetrical hybrid wars and armed conflict. The latter faces the prisoner’s dilemma: the one who makes the first step will be at a disadvantage. In addition, both sides believe that they still have a strategic advantage over the other. For the West, it is democracy and open society in addition to its competitive advantage, which yet is shrinking. For China, it is increasing self-sufficiency, its large domestic market, and the prolonged advantage of a late-emerging economy. Moreover, China feels closer to the non-Western world that will subsequently represent the largest global GDP in the future.

However, if both sides want to maintain or increase their level of wealth and income while improving equality, a global, open economy is needed. If both sides are genuinely interested in effectively addressing global challenges, global cooperation and solidarity is needed. Equivalently, to overcome the prolonged deadlock undermining global climate action, we need new common rules and a new global order that incentivizes such collaboration and preserves the resilience of the Sino-U.S. relations. If the West still believes that liberal democracy is the “end of history,” it should focus on its own shortcomings and seek to reform the system and make it more appealing to all. If the West is in doubt and lacks a new vision of how to reform liberal capitalism, it should better find a mechanism for inclusive global collaboration and cooperation. The stake might be higher until the two come to a détente. To this end, the US must overcome its exceptionalist mentality that has been driving Washington to pursue dominance in its relations with China. In the meantime, China needs to further open up, and continue advance reforms in social, political, and economic fields based on the conditions of the nation. Together, the two should maintain constructive dialogue, avoid misperception, enhance mutual understanding, and facilitate exchange and cooperation.

—————————————————————

ON TIMES WE FOCUS.

Should you have any questions, please contact us at public@taiheglobal.org